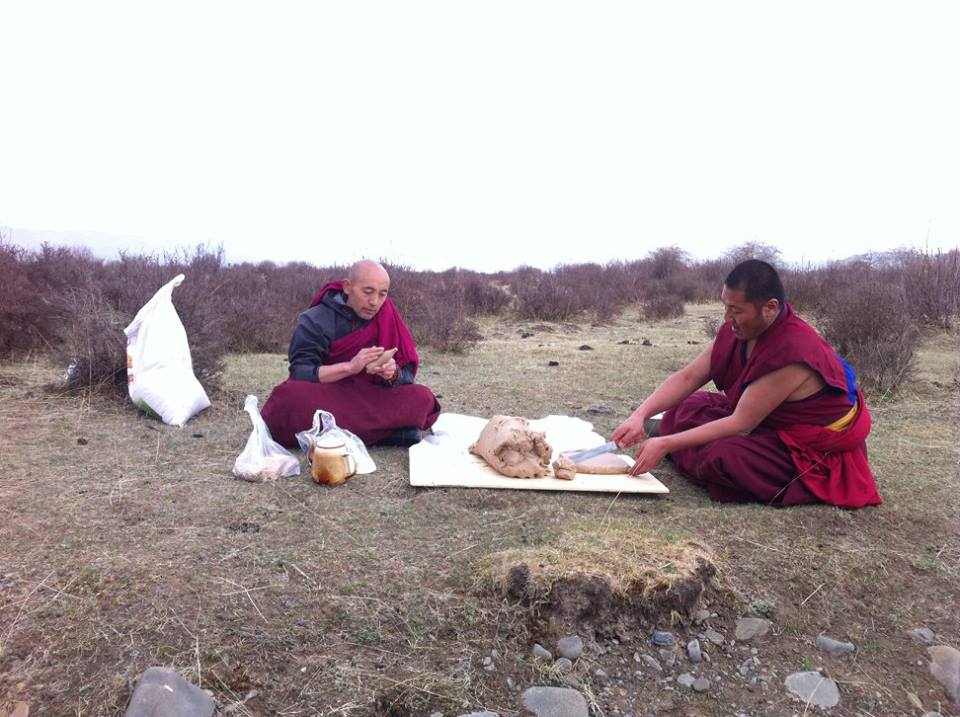

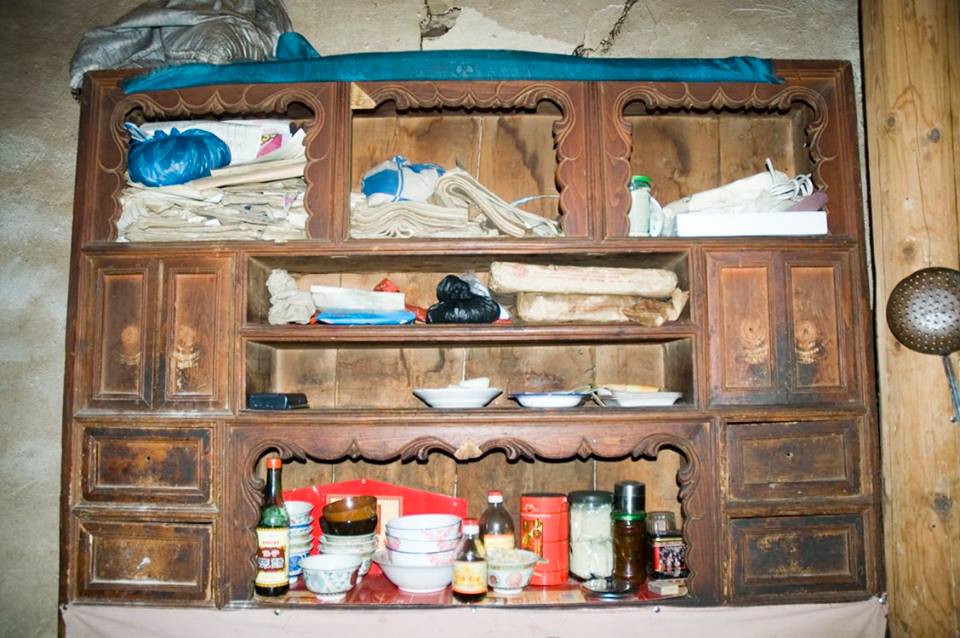

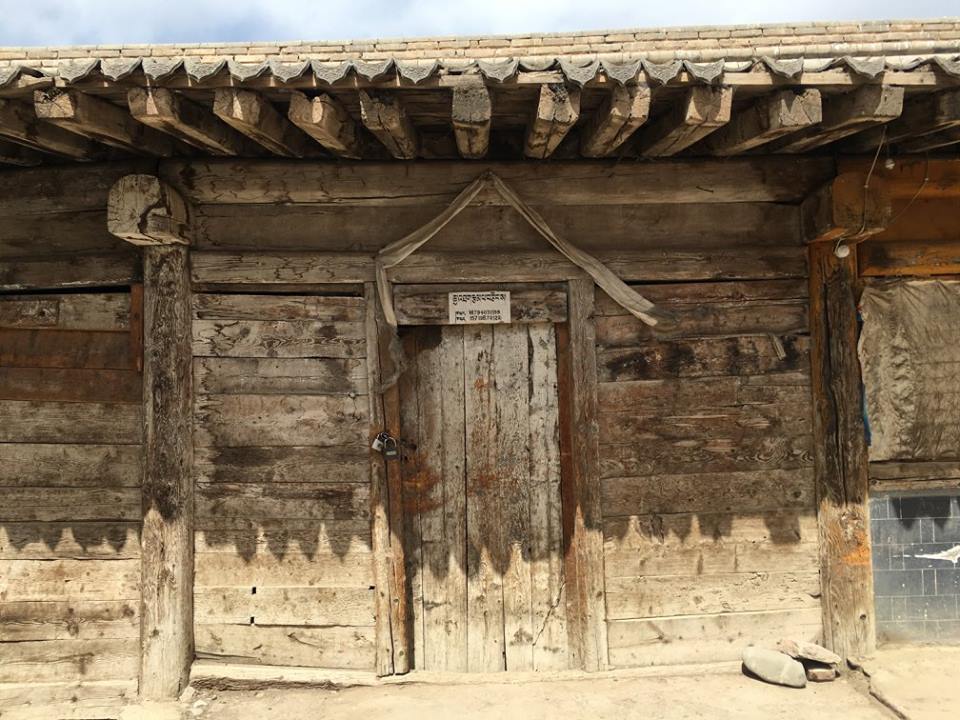

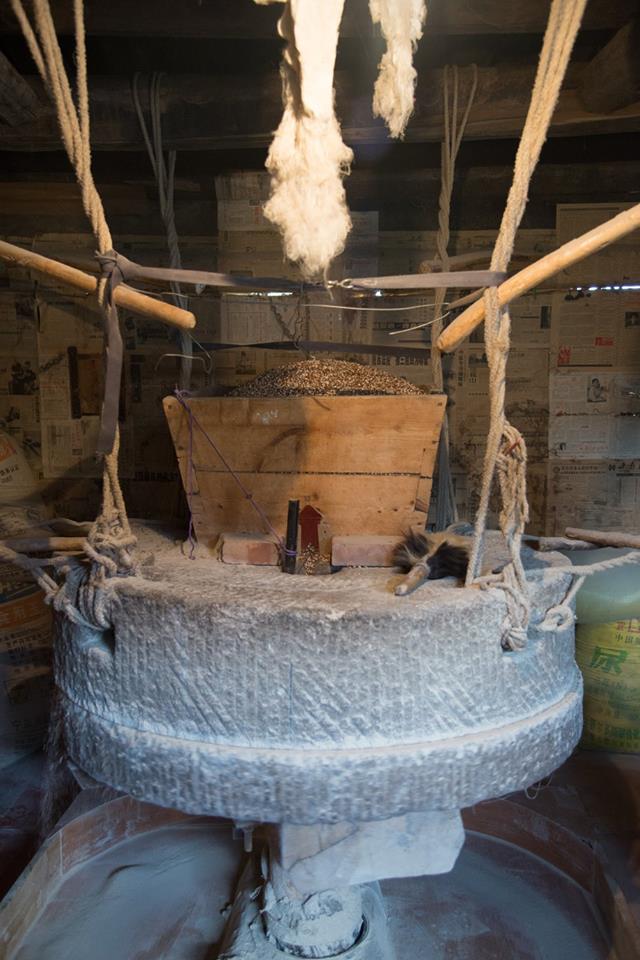

My taste in furniture had always been somewhat restrained on the one hand by my Western upbringing, and on the other, by the ways Tibetans viewed their surroundings in terms of old and new, town and country. Having worked for years trying to bring back to memory and existence the best of what was Tibetan furniture, I later realized that the simple and modest, the raw and worn, had been overlooked with a certain disdain (this is peasant stuff) characterized by both Tibetans in Tibet and in exile and had, as a result, escaped my attention. My father, in spite of his undying love for Lyon silks, Louis XV chairs and gold leaf, also appreciated rustic French peasant furniture, which we used in every day context. Dechen and I carried this on, in the form timid love for a low, solid, worn table given to her by Yidam’s family, a few pieces from the local Tso bric a brac store, and the cheese cloth, traditionally used by nomads to dry cheese on, locally woven from yak hair and sheep wool. I also noticed the cabinet in Yidam’s monk brother’s house in Labrang, which hung on the kitchen wall, displaying the bowls and cups, with drawers that doubled as butter boxes. Local notions prevailed, though. The table, displayed on the kang in their house had to be relegated to the back room when monks came, and replaced by a hideous varnished impostor and the cheese cloth, reminded of its low rank, was barred from covering a table, and relegated to placement on a large, wooden tsampa box on the veranda. My friend Isabelle Graz, a Swiss Designer who worked in China at the time, shook things around and pushed the vernacular to center stage, gradually eroding local notions and prejudices. It started when I accompanied her roaming in the Shanghai area bric a brac warehouses. These huge spaces, divided into alleys, had furniture piled as high at it could go. The trendy art deco from the twenties and thirties had long gone, driving the Shanghai furniture traders to dig deeper inland, into Shanxxi Province, bringing out old peasant furniture. Five years ago, no one really paid much heed to an old concubine’s chair, a wood and bamboo larder or a two hundred year old armoire. They were faded, scratched, wearing marks of hundred years of use. With their simple curves, solid appearance, these pieces weighed of simplicity and functionality. The local Tibetans and Chinese visitors winced at first when they saw our newly purchased, wobbly assortment spread out in a tent in front of the unfinished guesthouse, recognizing things of their past that had long been discarded as old and useless by their parents or themselves. Within a few weeks, notions changed. Placed in context surrounded by Norlha felt and woven soft furnishings, they settled gracefully, exuding a simple dignity, a quiet elegance that lent the rooms and common areas a cosy/trendy feel. Isabelle furnished the Norlha Guesthouse with these and custom made pieces forming a simple, harmonious ensemble. A year later, when we turned our attention to Norden Camp, we decided to look even more locally for the cabin, tent and venue area furniture. Isabelle had a knack for uncovering treasures; When we drove between Ritoma and Labrang, she would suddenly ask that we stop the car at the sight of a junk pile, from where she would extract a door, an old window, or a low table from the rubble of a dismantled house. Dechen, Yidam and I learned to look at things differently, to see treasures in the ordinary objects that surround a quickly disappearing lifestyle. Yidam quickly picked up a flair for rummaging through the rubble of demolished houses and began collecting old latticed windows, remnants of a not so far away past when people pasted thick oiled paper in lieu of glass. During the fall of 2013, he and Dechen sent out the Norden team to forage for trunks, tables and kitchen cabinets in Yidam’s native area, Tsayig. They came back with tsampa trunks covered in yak or dzo hide, cabinets of all sorts and sizes, butter churning implements, butter boxes, low tables and more. The team would photograph the piece on their phone, send it to Yidam and Dechen who would give their ok. Norden has continued and refined its yearly winter village foraging, complementing our assortment with locally woven baskets, carved wooden trays, clay bowls, old rifles, and even an old cart, which have wormed their way into not only the Norden venues, but also accessorizing the Norlha stores. In a mere two years, perceptions have changed and the contemporary/old look is finding its way all over Labrang. New Trends, new ideas.