The Tibetan Picnic

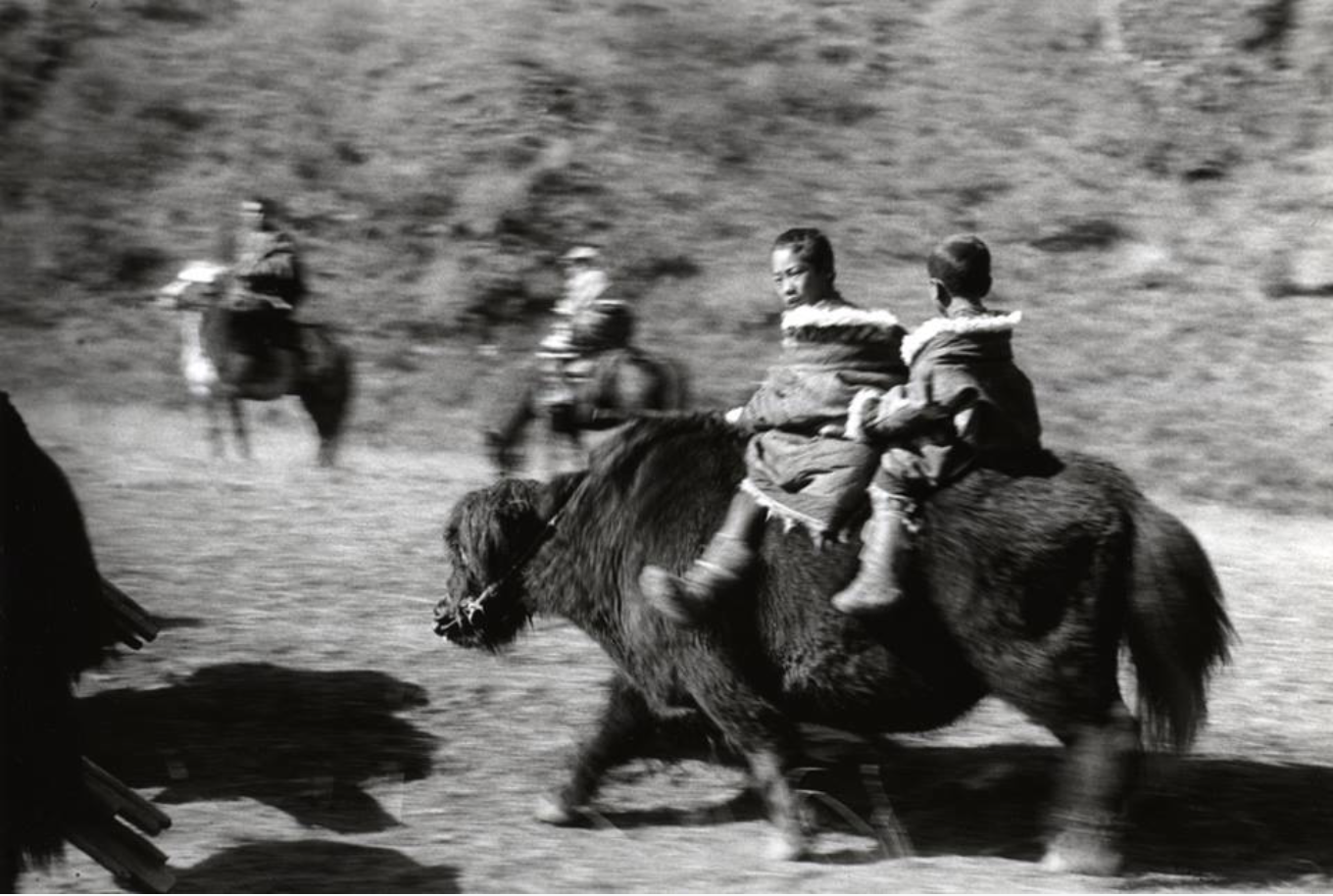

/The vast grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau were the home of nomadic people who, with their millions of yaks and sheep, formed the core of the Tibetan economy. Those who didn’t move about with their animals did so for trade, and movement pervaded all aspects of life.

Cities were hubs for commerce and its inhabitants had the most leisure time of all. In summer, they sought out what they no longer had, life on the grassland, and recreated it as a source of enjoyment and relaxation.

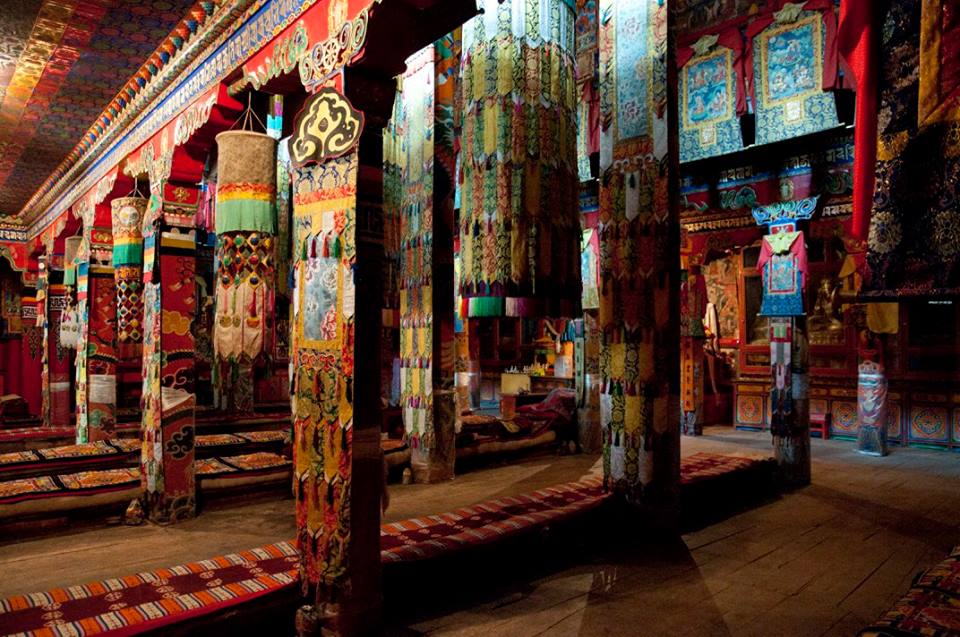

Sometime at the beginning of the 20th century, someone came up with the picnic tent concept, soon to become the norm, a canvas tent with a white base decorated with appliqued motifs. These could be outrageously bright and colorful or a more subdued black or navy on a white base. An older Tibetan remembers the summer picnics which took place yearly, at the time of the Zamling Chisang festival. Families packed their belongings, loaded them on carts and pitched their fancy tents, furnished with carpets, tables and cushions, even thangkas on the cloth walls, by the river. Picnic spots were carefully chosen and perfect ones had many attributes: cushy, abundant grass, a commanding view, protection from wind, and proximity to a river or stream. For two weeks, people socialized, sang and danced, cooked, ate and played games. A whole kitchen tent was set up to prepare elaborate food, families outdoing each other with fancy dishes and new culinary creations. For children, it was paradise. They met all their friends, swam and explored, the adults too engrossed in their own activities to mind what they were doing. “The return to Lhasa, with the packing up of the tents marked the close of the school holiday. The end of the picnic was like leaving paradise to reenter the hell of my dark, boring school”, he reminisced.

By the middle of the 20th century, picnics in Tibet were an institution that spread all over the Tibetan areas of the plateau. Picnics still last several days, and at festivals such as laptses, clan members gather to make offerings to the local deities, recreate a picnic like setting where families pitch their tents in a wide circle and enjoy themselves for several days, socializing and taking part in horse races. Monks also hold their own picnics that follow the end of the summer retreat. In Labrang, they pitch their tents on the Sankhe plain and enjoy themselves for ten days, cooking, eating and playing games. Important lamas and scholars also made use of tents when traveling to nomadic areas to give teachings, setting up camps and attract thousands of pilgrims.

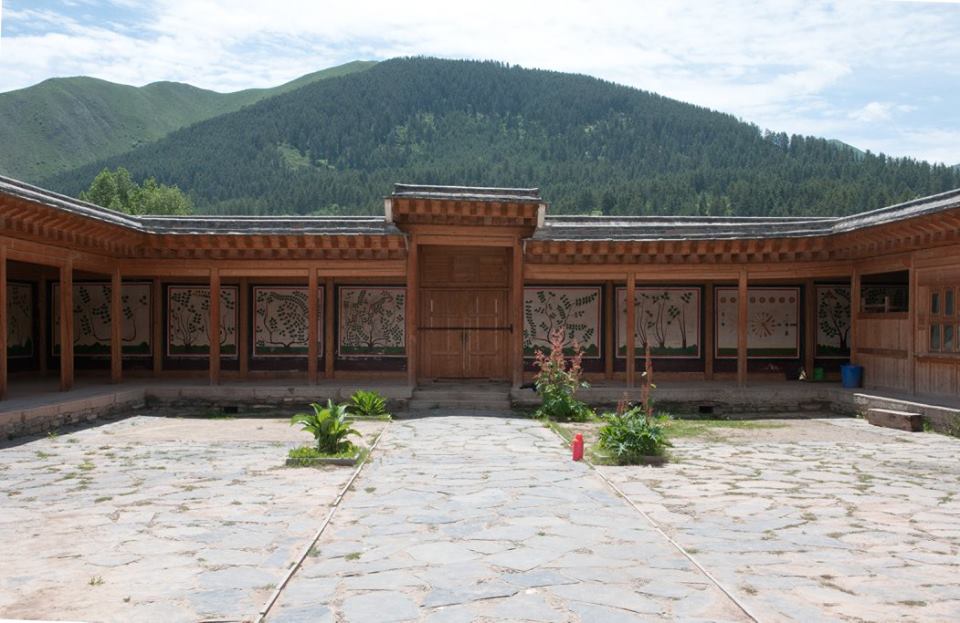

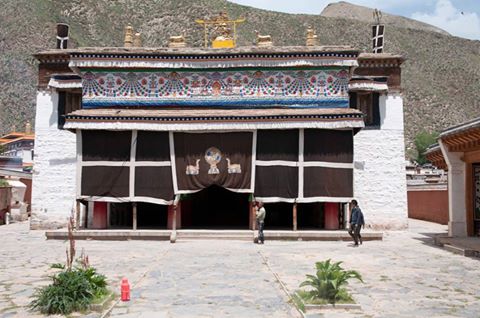

Norden Camp, in its inspiration and set up, has borrowed from both the nomadic life style and the festive feel of the picnic, creating a contemporary experience of the Tibetan picnic. The Luxury tent, offers a mix of comfort and feel of nomadic life, in a beautiful stop by the river, where one can be immersed in nature. The camp also prepares nature experience of the picnic with a day excursion. An hearty meal is prepared and a beautiful, isolated scenic spot chosen in advance. A makeshift hearth is built on which tea is prepared, and the afternoon spent of walks spotting marmots and admiring the wild flowers.