Travel Gear

/Images of isolated Tibet, the land of hidden valley locked in time have always dominated impressions of the place. Nothing could be further from the truth. Tibet was a crossroad for trade linking China to the East, Central Asia to the West and India to the south. Except for the more isolated nomads, every household of any importance supplemented their income with trade and dedicated at least one family member to the task to bringing wool to India, collecting tea bricks from China, exchanging horses for brocade, tsampa for butter, cloth and carpets for sheepskins. Travel was a part of life, and people could be on the move for months, part of caravans that crisscrossed the Plateau on a wide range of routes.

Tibetans were naturally adapted to this life of travel. Their crossed shirt is believed to have its origins in horse riding, where it proves more protective. The chuba can come on and off in parts, convenient for the Plateau weather that can turn from hot to cold in minutes, or the contrary. The horseman could easily liberate one arm, then his torso, wrap the chuba sleeves in a voluminous bunch around his waist and enjoy the sun, then pull it back on in minutes when it disappeared behind a cloud.

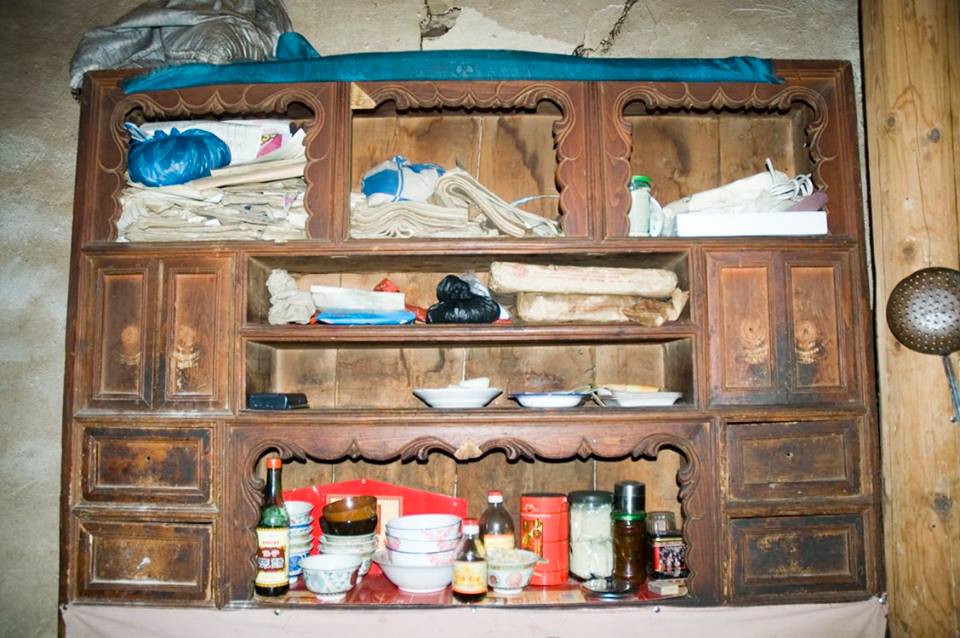

Every traveler had his gear, which was so deeply ingrained in the culture that remnants of it could be found even in city dwellers and the costume of officials, who had a small knife and chopsticks (in a case) hanging from their belts. People carried their own bowls, which were mostly, especially in the case of monks, made of the gnarled wood of trunks and knots of birth or tung trees, mostly found in the Mon region, now a part of India. Officials and laymen could carry precious porcelain bowls from China, and had special cases made from wool twisted over a wire frame, to protect them. Bowls were tucked into the ambam, the fold to the chuba, ready to be taken out for ceremonial tea or a break in a journey.

The main edibles for life on the move were the Tibetan basics of tsampa, dried cheese, dried meat and butter. Except for butter that travelled in a wooden box, the other staples had little drawstring bags made of wool or skin, and would all be placed in a saddle bag for easy access. A full meal thus only required hot water, provided by a fire built on the road, lit with the flint stones that every man wore hanging from his belt. Since riding happened for hours at a time, most travelers also wore a necklace of hard cheese, which they chewed as they went along, to calm hunger until the next stop.

Tibet is the land of travel and travelers.